Orbital will employ its Taurus II medium-lift launch vehicle and the Cygnus spacecraft in order to service the International Space Station (ISS) under the Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) contract.

Orbital is one of the two companies awarded CRS contracts under the Commercial Orbital Transportation Services Project (COTS).

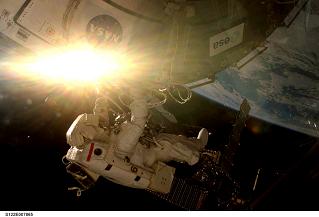

NASA announced the COTS project on January 18, 2006. The purpose of the program is to stimulate the development of access to low Earth orbit (LEO) in the private sector. At the time, with the imminent retirement of the Space Shuttle fleet, NASA was faced with the option of buying orbital transportation services on foreign launch systems: the Russian Soyuz / Progress, the European Ariane 5 / ATV, or the Japanese H-II / HTV.

Another factor taken into consideration by NASA was that competition in the free market could lead to the development of more efficient and affordable launch systems compared to launch systems that a government agency could build and operate.

Orbital relies on proven experience in launch vehicle technology. Taurus II is designed to provide low-cost and reliable access to space, and it uses systems from other members of Orbital’s family of successful launchers: Pegasus, Taurus, and Minotaur.

Taurus II is a two-stage launch vehicle that can use an additional third stage for achieving higher orbits. The payloads handled by Taurus II can have a mass of up to 5,400 kg.

Orbital is responsible for overall development and integration of the first stage. The two AJ26-62, designed and produced by Aerojet and Orbital, are powered by liquid oxygen and kerosene. The core design is driven by NPO Yuzhnoye, the designer of the Zenit launchers.

The AJ26-62 engines are basically the NK-33 engines designed by the Kuznetsov Design Bureau for the Russian N-1 launch vehicle, and remarketed by Aerojet under a new designation.

The second stage uses an ATK Castor-30 solid motor with thrust vectoring. This stage evolved from the Castor-120 solid stage.

The optional third stage is developed by Orbital. The stage was dubbed the Orbit Raising Kit (ORK) and it uses a helium pressure regulated bi-propellant propulsion system powered by nitrogen tetroxide and hydrazine. ORK evolved from the Orbital STAR Bus. Because it is a hypergolic stage, it allows several burns to be performed in orbit, and can be used for high-precision injections using various orbital profiles.

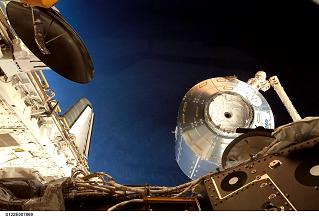

Cygnus will only have cargo capability and will be able to deliver up to 2,300 kg of pressurized or un-pressurized cargo to the ISS. The spacecraft will also be able to return up to 1,200 kg of cargo from ISS to Earth.

The two components of the Cygnus spacecraft will be the service module and the cargo module.

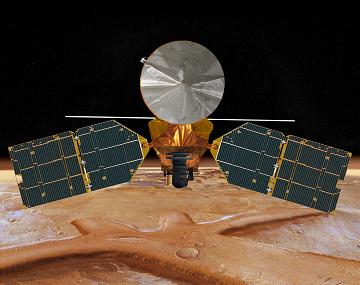

The service module is based on the Orbital STAR bus (like the ORK stage), and will use two solar arrays for producing electrical power for the navigation systems onboard.

The pressurized cargo module is based on the Italian-built Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM). The un-pressurized cargo module is based on NASA’s ExPRESS Logistics Carrier.

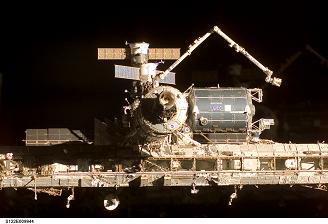

Cygnus will not dock to the ISS in the same manner as the European ATV, but it will be able to maneuver close to the ISS where the Canadarm 2 robotic arm will be used to capture it and berth it to the Node 2 module, similar to the Japanese HTV or SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft.

The Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport (MARS), located at NASA’s Wallops Island Flight Facility on Virginia’s Eastern shore, was chosen by Orbital to serve as the base of operations for the Taurus II launch vehicle.

MARS has two FAA licensed launch pads for LEO access. MARS also offers access to suborbital launchers, vehicle and payload storage, and processing and launch facilities.

Due to the location of the spaceport, latitude 37.8 degrees N, longitude 75.5 degrees W, optimal orbital inclinations for the launches performed at MARS are between 38 and 60 degrees. Polar and retrograde orbits can also be serviced with additional in-flight maneuvering.

The first flight of Orbital’s new Taurus II / Cygnus launch system under COTS is scheduled for late 2010.

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS