|

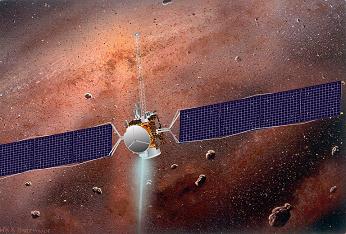

| Credits: NASA/JPL |

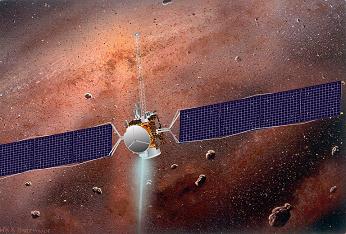

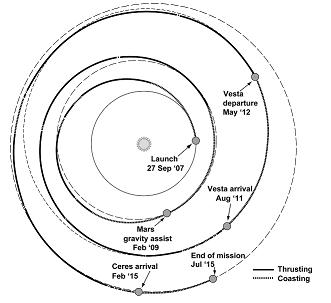

The Dawn spacecraft is currently performing the Mars flyby phase of its mission. The purpose of the Mars flyby is to alter the trajectory of the spacecraft in order to rendezvous with its first scientific target in the main asteroid belt.

The spacecraft will come within 549 km of the surface of Mars on February 17, 2009, at 4:28 PST.

The flyby is a gravity assist maneuver used in orbital mechanics to alter the trajectory of a spacecraft. The gravity assist is also known as a gravitational slingshot. The first ever gravity assist maneuver was performed by Mariner 10 in February 1974, and most of the interplanetary missions have made use of it since then.

The scientific objective of the Dawn mission is to answer important questions about the origin and the evolution of our solar system. The currently accepted theory about the formation of our solar system states that Jupiter’s gravity interfered with the accretion process, thereby preventing a planet from forming in the region between Jupiter and Mars. This led to the formation of the asteroid belt.

The asteroids chosen as scientific targets for the Dawn mission are Vesta and Ceres. Due to their size, they have survived the collisional phase, and it is believed that they have preserved the physical and chemical conditions of the early solar system. The asteroids have followed different evolutionary paths and have dissimilar characteristics, which makes them perfect research subjects.

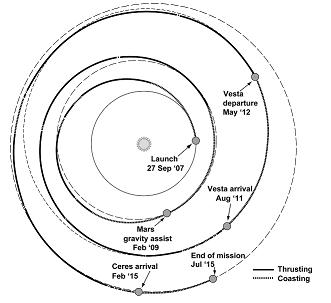

|

| Credits: NASA/JPL |

The design of the Dawn spacecraft is based on Orbital’s STAR-2 series, and uses flight-proven components from other Orbital and JPL spacecraft: the propulsion system is based on the design used on Deep Space 1, the attitude control system used on Orbview, a hydrazine-based reaction control system used on the Indostar spacecraft, and command and data handling, as well as flight software, from the Orbview program.

The core structure of the spacecraft is a graphite composite cylinder, while the panels are aluminum core with aluminum/composite face sheets.

The central cylinder hosts the hydrazine and xenon tanks. The hydrazine tank can store 45 kg of fuel, while the xenon tank has a capacity of 450 kg.

The attitude control system (ACS) uses star trackers to estimate attitudes in cruise mode. A coarse Sun sensor (CSS) allows ACS to keep the solar panels normal to the Sun-spacecraft line. ACS also uses the hydrazine-based reaction control system for the control of attitude and for desaturation of the reaction wheels.

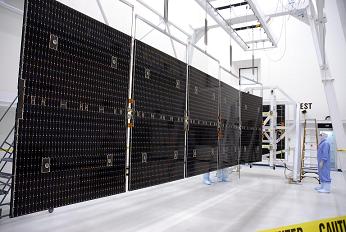

|

| Credits: NASA/George Shelton |

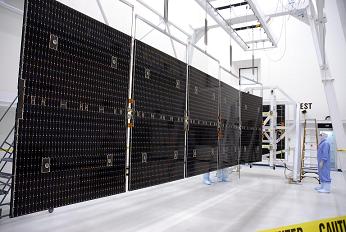

The solar panels are capable of producing more than 10 kW at 1 AU and 1 kW at 3 AU (on Ceres’ orbit).

The command and data handling system (CDHS) is based on a RAD6000 board running VxWorks. The software is written in C. There are 8GB available on the board as storage for engineering and scientific data.

The scientific payload consists of the Framing Camera (FC), the Gamma Ray and Neutron Detector (GRaND), and the visible and infrared (VIR) mapping spectrometer.

The FC will be used for determining the bulk density, the gravity field, for obtaining images of the surface, and for compiling topographic maps of Vesta and Ceres. In addition, the FC will capture images for optical navigation in the proximity of the asteroids. For reliability purposes, the payload includes two identical cameras that can run independently.

GRaND will serve for the determination of the elemental composition of the asteroids. GRaND is the result of the expertise accumulated during the Lunar Prospector and Mars Odyssey programs.

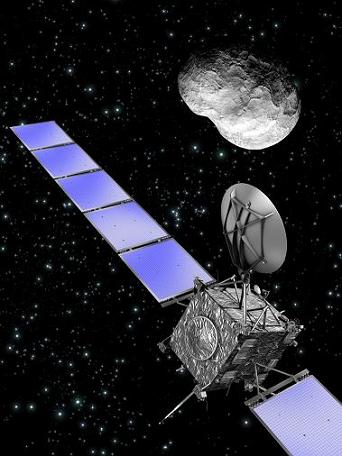

|

| Credits: NASA/Jack Pfaller |

VIR will help map the surface mineralogy of the asteroids. The instrument is a modified version of the visible and infrared spectrometer flying on the Rosetta mission.

The Dawn spacecraft uses ion propulsion to make its journey to Vesta and Ceres. Ion propulsion will also be used by Dawn during the low altitude flights over the asteroids.

While the fact that Dawn’s engines have a thrust of only 90 mN can hardly impress a reader, the important detail to mention when discussing propulsion systems is the specific impulse. Dawn’s engines have a specific impulse of 3100 s. For a chemical rocket, the specific impulse ranges from 250 s for solid rockets to 450 s for bipropellant liquid rockets. The only drawback (if this can be regarded as a drawback) is that the ion engines must be fired for much longer in order to achieve an equivalent trajectory.

With such high specific impulse engines, Dawn makes use of the fuel onboard in a very efficient way. The fuel used is xenon, a heavy noble gas placed in group 8A of the periodic table. The power produced by the large solar panels is used to ionize the fuel and then accelerate it with an electric field between two grids. In order to maintain a neutral plasma, electrons are injected into the beam after acceleration.

|

| Credits: NASA/Amanda Diller |

Dawn was launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station and injected on an interplanetary trajectory by a Delta II launch vehicle.

The main contributors to the Dawn mission are the University of California in Los Angeles (science lead, science operations, data products, archiving, and analysis), the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (project management, systems engineering, mission assurance, payload, navigation, mission operations, level zero data), and the Orbital Sciences Corporation (spacecraft design and fabrication, quality assurance, and payload integration).

The scientific payload was provided by the Los Alamos National Laboratory, the German Aerospace Center, the Max Planck Institute, and the Italian Aerospace Center. The Deep Space Network is responsible for data return from the spacecraft.

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS