Credits: ESA MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPM/

Credits: ESA MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPM/

LAM/IAA/RSSD/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

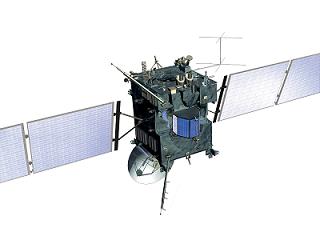

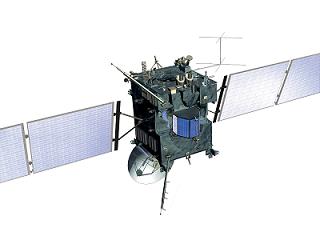

On September 6th, 2008, the ESAâs space probe Rosetta performed the first highlight on its 11 year mission: a close flyby the asteroid 2867 Steins. There are two more important events to occur during the mission, which are another flyby the asteroid 21 Lutetia in 2010 and the actual rendezvous with the comet 67/P Churyumov-Gerasimenko in 2014.

The Rosetta mission is special in many ways. It is the first mission to deploy a lander to the surface of a comet. It will also be the first to orbit the nucleus of a comet and to fly alongside a comet as it heads towards the inner Solar System.

Credits: ESA

Credits: ESA

Rosettaâs mission began on March 2nd, 2004, when the spacecraft lifted off from Kourou, French Guiana. In order to optimize the use of fuel, the probe has a very complicated trajectory to reach its final target, the comet 67/P Churyumov-Gerasimenko. The long trajectory includes three Earth-gravity assists (2004, 2007, and 2009) and one at Mars (2007). The probe uses the gravity wells of Earth and Mars to accelerate to the speed needed for the rendezvous with the comet. Most of the time, the probe is hibernating with the majority of its systems shut down in order to optimize the power consumption. At the time of the rendezvous, the remaining fuel will be used to slow down the probe to match the speed of the comet.

Credits: ESA/AOES Medialab

Credits: ESA/AOES Medialab

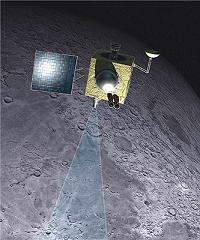

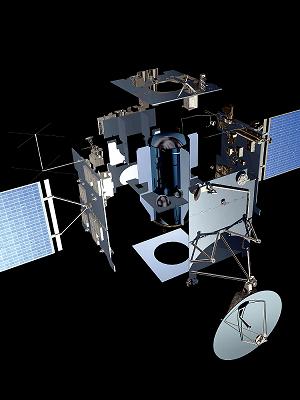

After reaching the comet, Rosetta will deploy a lander, called Philae, to the surface. While the probe will study the cometâs nucleus from a close orbit, the lander will take measurements from the cometâs surface. Because the gravity of the comet is very weak, the lander will use a harpoon to anchor itself to the surface.

Rosetta will stay with the comet more than one year, and during this time it will study one of the most primitive materials in the solar system. Scientists hope to discover the secrets of the physical and chemical processes that marked the beginning of the solar system some 5 billion years ago.

Credits: ESA/AOES Medialab

Credits: ESA/AOES Medialab

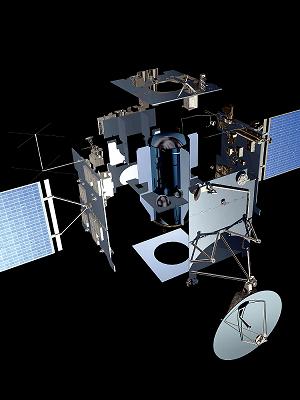

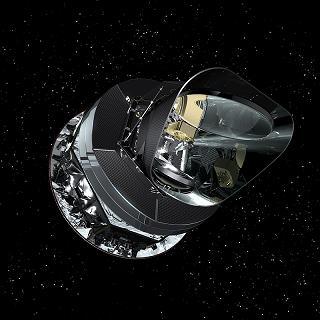

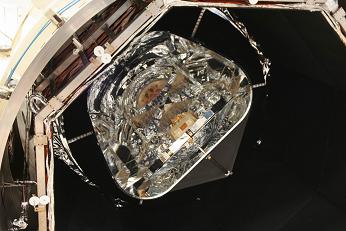

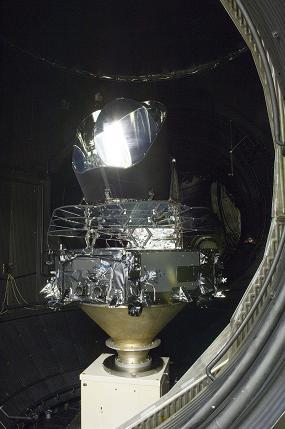

Traditionally, probes sent beyond the main asteroid belt employ radioisotope thermal generators (RTGs) as power generators. RTGs convert the heat from a radioactive source into electricity using an array of thermocouples. Instead, Rosetta is using solar cells for power generation. The probe deploys two impressive solar panels (a total area of 64 square meters). Even when close to the comet, the panels will be able to generate around 400 Watts of power. The panels can be rotated through +/- 180 degrees to track the Sun in every attitude assumed by the probe.

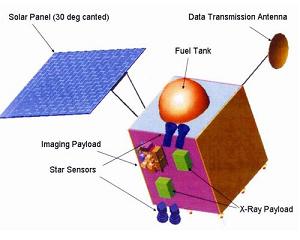

The probe is cube-shaped and measures 2.8×2.1×2.0 meters. At launch, it weighs 3,000 kg, including 1,670 kg of fuel, 165 kg of scientific payload for the orbiter, and 100 kg for the lander. The scientific instruments are accommodated on the lower side of the probe, which will be directed towards the comet during the last phase of the mission. Meanwhile, the probe will orbit the nucleus of the comet. A communication antenna 2.2 meters in diameter will be mounted on one side of the probe and on the opposite side the lander is attached. The other two lateral sides are used for anchoring the solar panels.

Credits: ESA/AOES Medialab

Credits: ESA/AOES Medialab

I was able to dig up more information about the probe and the lander in the mission launch kit on the EADS Astrium website.

The prime contractor for the spacecraft is Astrium Germany. The main sub-contractors are Astrium UK, Astrium France, and Alenia Spazio.

For propulsion and attitude control, the probe is using 24x10N bipropellant jets. The propulsion system is at the centre of the probe, where the tanks of propellant are located in the centre of a vertical tube.

I could not find an explanation as to why this design was chosen. Since the ability of the spacecraft to maneuver by using the onboard propulsion system is critical, I am assuming that the fuel tanks have to be protected from possible hits by micro meteorites.

Credits: ESA/AOES Medialab

Credits: ESA/AOES Medialab

The scientific instruments onboard Rosetta are: OSIRIS (Optical Spectroscopic and Infrared Remote Imaging System), ALICE (Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrometer), VIRTIS (Visible and Infrared Thermal Imaging System), MIRO (Microwave Instrument for Rosetta Orbiter), ROSINA (Rosetta Orbiter Spectrometer for Ion and Neutral Analysis), COSIMA (Cometary Secondary Ion Mass Analyser), MIDAS (Micro-Imaging Dust Analysis System), CONSERT (Comet Nucleus Sounding Experiment by Radiowave Transmission), GIADA (Grain Impact Analyser and Dust Accumulator), RPC (Rosetta Plasma Consortium), and RSI (Radio Science Investigation).

The lander is provided by a European consortium lead by the DLR (German Aeronautic Research Institute). Members of this consortium include ESA and the Austrian, Finnish, French, Hungarian, Irish, Italian, and British institutes.

Credits: ESA/AOES Medialab

Credits: ESA/AOES Medialab

The lander has a polygonal carbon fibre sandwich structure which is covered in solar cells. The antenna transmits data from the lander via the probe orbiting the comet.

There is an impressive collection of scientific instruments mounted on the lander as well: COSAC (Cometary Sampling and Composition experiment), MODULUS PTOMELY (Gas analyser), MUPUS (Multi-Purpose Sensors for Surface and Subsurface Science), ROMAP (Rosetta Lander Magnetometer and Plasma Monitor), SESAME (Surface Electrical Seismic and Acoustic Monitoring Experiments), APXS (Alpha X-ray Spectrometer), CONSERT (Comet Nucleus Sounding Experiment by Microwave Transmission), CIVA (Imager system using panoramic cameras), ROLIS (Rosetta Lander Imaging System used during the descend phase), and SD2 (Sample and Distribution Device, a sample acquisition system).

Credits: ESA

Credits: ESA

The scientific data collected by the instruments is transmitted to the Rosetta Mission Operations Centre (MOC) through a 8bps link. Due to the narrow bandwidth, the data cannot be sent back to Earth in real-time and has to be stored on the probe before being relayed.

The MOC at the European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) in Darmstadt has been controlling this long term mission since launch using ESAâs DSA 1 deep-space ground station at New Norcia.

It may seem like a long journey, but as in The Days of the Comet, the Rosetta mission could open up a whole new world of possibilities.

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS