|

| Credits: NASA |

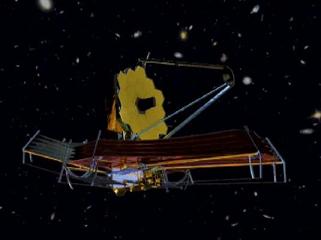

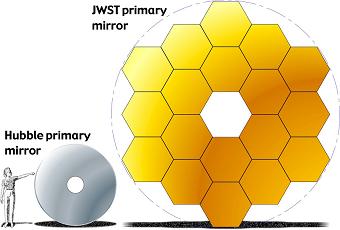

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is the successor of the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). While Hubble looks at the sky in the visible and ultraviolet light, JWST will operate in the infrared.

JWST is a joint mission of NASA, ESA, and the Canadian Space Agency.

The project started in 1996 and was initially known as the Next Generation Space Telescope (NGST). In 2002, the project was renamed the James Webb Space Telescope in honor of NASA administrator James E. Webb, who led the agency from February 1961 to October 1968.

The JWST will use a large deployable sunshade to keep the temperature of the telescope to about 35K. Operating at this temperature gives the telescope exceptional performance in near-infrared and mid-infrared wavebands. The JWST observatory will have a five to ten year lifetime and it will not be serviceable by astronauts.

JWST will be able to see the first galaxies that formed in the early Universe, and how the young stars formed planetary systems.

|

| Credits: NASA |

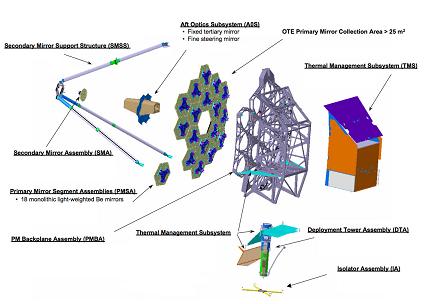

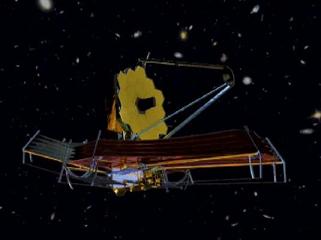

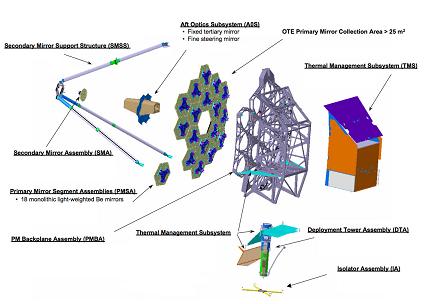

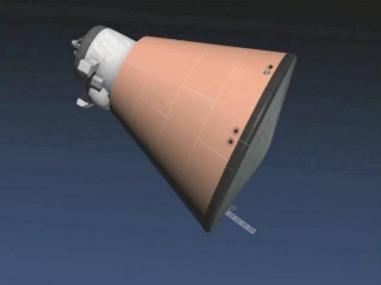

The JWST observatory includes the Integrated Science Instrument Module (ISIM), the Optical Telescope Element (OTE), and the Spacecraft Element containing a spacecraft bus (which offers the support functions for the observatory) and the sunshield.

I will say a few words about each one of them.

The Optical Telescope Element (OTE) collects the light coming from space. Thanks to a 6.5 meter primary mirror, JWST will be able to see the galaxies from the beginning of the Universe. The OTE is also composed of the Fine Steering Mirror (FSM), the secondary mirror support structure (SMSS), and the primary mirror backplane assembly (PMBA). Other subsystems of the OTE are the tertiary mirror and the fine steering mirror. The PMBA contains the Integrated Instrument Module (IIM).

Because the primary mirror is too large to fit inside any available payload fairing, it had to be made out of eighteen hexagonal segments. Some of the elements will be folded before the launch and unfolded during the commissioning phase at the L2 point. NASA made available some neat animations showing how the observatory will be folded in order to fit into the launcher payload, and how the sun shields and the primary mirror will unfold before the observatory becomes operational.

|

| Credits: NASA |

The sunshield will keep the scientific payload of the observatory away from any light from the Sun, the Earth, or the Moon. Because JWST will observe primarily the infrared light from very distant objects, the temperature of the scientific payload must be maintained at very low values (under 50K). This requirement is so important that even a part of the observatory (the spacecraft bus) had to be placed on the warm side of the sunshield.

The sunshield not only protects the scientific instruments from the heat of the Sun, the Earth, the Moon, and the warm spacecraft bus electronics, but it also provides a stable thermal environment. This is necessary in order to maintain the alignment of the eighteen hexagonal components of the mirror while the observatory changes its orientation relative to the Sun.

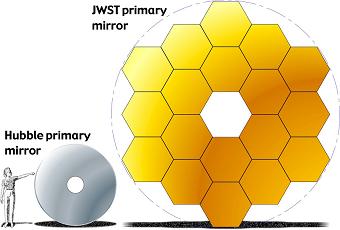

The primary mirror is the essential component of a telescope. The design of the primary mirror was driven by a number of important requirements: the size, the mass, and the temperature at which the mirror will operate.

|

| Credits: NASA |

In order to be able to see galaxies from thirteen billion light-years away, scientists determined that the mirror must have a diameter of at least 6.5 meters.

The weight of the primary mirror has only one tenth of the mass of Hubble’s mirror per unit area. Considering the size of the mirror, this made the task of launching the telescope into space achievable.

Due to the fact that the telescope will observe the light in the infrared spectrum, the temperature of the mirror has to be as low as –220 degrees Celsius. If operating at the same temperature as the ground telescopes do, the infrared glow of the mirror would interfere with the light received from distant galaxies. Basically, these distant galaxies would disappear in the noise generated by the telescope.

The engineering challenge that scientists faced was to build a lightweight mirror that would preserve its optical and geometric properties when cooled to –220 degrees Celsius. Using beryllium was the solution. Beryllium is lightweight (it is widely used in the aerospace industry) and it is very good at holding its shape across a range of temperatures.

As we mentioned above, the PMBA contains the Integrated Instrument Module (IIM), which is the scientific payload onboard the observatory. The scientific payload includes the following scientific instruments: the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), the Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec), the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam), and the Fine Guidance Sensor (FGS).

The MIRI is an imager/spectrograph that covers the wavelength range from 5 to 27 micrometers. The nominal operating temperature for the MIRI is 7K. The NIRSpec covers two wavelength ranges: from 1 to 5 micrometers (medium-resolution spectroscopy) and from 0.6 to 5 micrometers (lower-resolution spectroscopy). The NIRCam was provided by the University of Arizona. NIRCam covers the spectrum from 0.6 to 5 micrometers. The FGS is a broadband guide camera that is used for guide star acquisition and fine pointing.

|

| Credits: ESA |

The spacecraft bus is composed of every subsystem of the observatory minus the sunshield and the scientific payload, and it provides the necessary support functions for the operations of the observatory. The spacecraft bus contains the Electrical Power Subsystem (EPS), the Attitude Control Subsystem (ACS), the Communication Subsystem (CS), the Command and Data Handling Subsystem (C&DHS), the Propulsion Subsystem (PS), and the Thermal Control Subsystem (TCS).

One interesting thing I would like to mention here is that the C&DH subsystem is using a solid-state recorder as memory/data storage for the observatory. I cannot envision a hard disk drive taking all of the vibrations during the launch and running for ten years without any flaws, so the choice of using radiation hardened solid-state memory units on long-term space mission spacecrafts seems to be the optimal choice.

The launch vehicle chosen for this mission is the European Ariane 5. The Ariane 5, carrying the James Webb Space Telescope, will liftoff from Guiana sometime in 2013. The space telescope will operate from the L2 point of the Sun-Earth system.

All three agencies that are part of the project, ESA, NASA, and CSA, have web pages dedicated to the JWST observatory.

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS