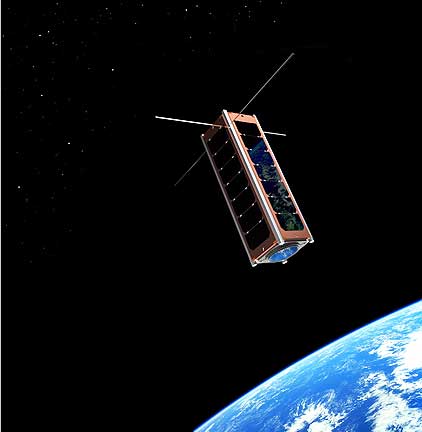

The second Canadian Satellite Design Competition (CSDC) team that answered our invitation to a Q&A is the team from Dalhousie University. Colin O’Flynn, graduate student at Dalhousie University and CTO of the CSDC team, answered our questions.

Q: What hardware do you intend to use? Off-the-shelf boards and software or are you developing your own?

A: We are aiming to use COTS boards and software as much as possible, especially during development. Eventually we will be forced to design and build custom hardware, since there is a very specific form-factor which many COTS boards won’t fit inside. Weight is also a huge issue for us – since many COTS boards contain lots of features we might not need (e.g.: LCD display, Ethernet connector), we can shave some weight by spinning our own board and not wasting space or weight with those features.

Ideally though we’ll just adapt the COTS board design to our satellite, meaning we can use a tested design with minimal work. Not Invented Here (NIH) syndrome is dangerous to engineering projects, so while our current research does show we can’t find the correct form factor, we’ll always be checking the market for new products that might let us avoid needless designs and builds.

Q: How do you intend to communicate with your satellite from the ground? UHF, Iridium modem, etc.?

A: Again our satellite has slightly different objectives from a normal commercial satellite, which are primarily concerned with issues such as maximizing bandwidth or minimizing lag, since that gives the best return on investments.

In our project we also want to provide something with a wide scientific and public appeal. To that end we plan on using amateur radio frequencies – this means people around the world can track our satellite. Often amateur radio operators are on the lookout for interesting projects which introduce young students to radio communications. Letting students receiver data from a real satellite overhead does a lot to promote both amateur radio and space, which just maybe will help inspire the next generation of engineers.

Whether this will be in the S-Band or just UHF hasn’t been finalized yet, although there is potential to actually have a beacon running in the more common UHF, and our more bandwidth-intensive comms (e.g.: for downloading payload data) in S-Band. The actual coding technique will use more recent codes (e.g.: turbo or LDPC). Again since this is supposed to be a more ‘innovative’ approach to space, we are working with some of the respected professors and students in our department to get recent advances in both coding and antenna design on our spacecraft.

Q: How do you generate and store power onboard the satellite? Batteries, solar panels? Do you intend to use deployable solar panels?

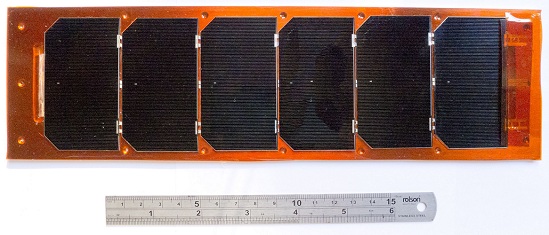

A: The solar panels will not be deployable, but fixed on the outside surface, with batteries storing the charge. This area will use more mature technology. The power system is so critical, and since testing the components such as panels or batteries for the required environmental conditions is beyond our capabilities, we don’t want to rely on experimental designs.

Q: Does the attitude determination and control system rely solely on reaction wheels? How do you intend to unload them? Magnetorquers, cold gas thrusters, or have you developed a novel technique?

A: The satellite is very small; many Cubesats only use magnetorquers without reaction wheels. This limits what and where you can correct obviously, so we are still exploring more interesting techniques. We have “penciled in” reaction wheels and magnetorquers, but this could drastically change.

The attitude determination is also planned to be pretty standard. Due to the small size of sensors on the market, we actually plan on outfitting our satellite with a wide range of sensors beyond what is required for attitude determination. We plan on adding a three-axis magnetometer, gyro, and accelerometer, along with GPS receiver. The idea is to provide enough data for postprocessing on Earth for testing new algorithms, experiments, etc.

Q: Do you plan to have any orbit control systems onboard? What is the orbital profile of the mission?

A: Nothing planned yet; the orbit we are given is defined as:

The design orbit for the mission has the following parameters (TBC):

• Semi-major Axis: 7078 ± 100 km (600km to 800km altitude)

• Eccentricity: < 0.01

• Inclination: sun-synchronous for the resulting altitude

Launch details won’t be confirmed for some time, so some of this is mostly chance depending what we end up riding along with.

The only possible orbit control system we are investigating would be for deorbiting the satellite at the end of its life. Space is a shared resource, and we want to make sure we aren’t needlessly polluting it with our satellite. If it naturally will deorbit in a reasonable time this won’t be necessary, but it’s something we want to be sure of.

Q: How do you plan to control the temperature onboard the satellite?

A: Currently something we are investigating. Preliminary calculations show we can do this passively to keep things within acceptable limits. Other Cubesats have done this in practice too.

We are trying to use automotive grade parts when possible, which gives us a better temperature range to work with. Understandably this isn’t possible for everything; the solar cells and battery are one obvious example.

Q: Who are the members registered with your team? What areas of expertise do they represent?

A: It’s a huge range of skills we have, including over a quarter that aren’t engineers or scientists. Our team is pushing outreach in the community, so for example running programs to introduce kids to space exploration, and the idea that it’s something they could become involved in themselves. Other sections of the team such as marketing, management, and finances are critical to our success, but have nothing to do with the core technical designs.

The technical team has about ten core members. The number of people working on the project though will be higher: we are defining senior year projects, which students will be able to get credit hours for. Time is always a problem in student run projects, so we are trying to make sure people get credit for all this work. Or as I like to point out: once they agree to help, they have to help, because otherwise they will fail the senior year project! It’s one way of retaining “volunteers”.

Subscribe to our RSS feed

Subscribe to our RSS feed

There are no comments.

Add A Comment