In 2002, an instrument on the Mars Odyssey spacecraft detected hydrogen under the Martian surface. This was regarded as clear evidence that there is subsurface water ice on Mars.

In 2003, NASA decided to revive a mission that was cancelled in 2001 due to the fact that a previous mission, the Mars Polar Lander, was lost in 1999. The revived mission was named Phoenix.

A Lander that could reach out and touch the ice was needed. The half-built spacecraft for the previously cancelled mission already had in place a 7.7-foot robotic arm that could do the trick.

A JPL team reviewed the data from the failed mission in 1999 and corrected the mistakes made. Every system used in the previous design was taken apart, tested, and examined. The suspected culprits were the retrorockets used during landing. More than a dozen issues that could have caused a failure of the new planned mission were found and fixed.

The Phoenix mission inherited a capable spacecraft partially built for the Mars Surveyor Program 2001. As we mentioned, the lessons learned from the Mars Polar Lander helped improve the existing systems. As for any other space mission, the conditions in which the spacecraft operates dictate the design.

In the case of the Phoenix mission, the following phases were considered: the launch, the cruise, the atmospheric entry, the touchdown, and the surface operations phase. The launch induces tremendous load forces and vibrations. The 10-month cruise to Mars exposes the spacecraft to the vacuum of space, solar radiation, and possible impacts with micrometeorites. During the atmospheric entry, the spacecraft is heated to thousands of degrees due to aero braking, and has to withstand tremendous deceleration during the parachute deployment. The extremely cold temperatures of the Martian arctic and the dust storms must be considered during the surface operations phase.

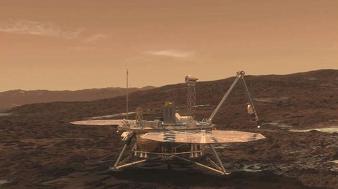

Several instruments are mounted on the Lander: the robotic arm (RA), the robotic arm camera (RAC), the thermal and evolved gas analyzer (TEGA), the Mars descent imager (MARDI), the meteorological station (MET), the surface stereo imager (SSI), and the microscopy, electrochemistry, and conductivity analyzer (MECA).

The RA was built by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and was designed to perform the scouting operations on Mars, such as digging trenches and scooping the soil and water ice samples. RA delivered the samples to the TEGA and the MECA. RA is 2.35 meters long, it has an elbow joint in the middle, and it is capable of digging trenches 0.5 meters deep in the Martian soil.

The University of Arizona and the Max Planck Institute in Germany built the RAC. The camera is attached to the RA, just above the scoop placed at the end of the arm. RAC provided close-up, full-color images.

TEGA was developed by the University of Arizona and University of Texas, Dallas. TEGA used eight tiny ovens to analyze eight unique ice and soil samples. By employing a process called scanning calorimetry, and by using a mass spectrometer to analyze the gas obtained in the furnaces as the temperature raised to 1000 degrees Celsius, TEGA determined the ratio of various isotopes of hydrogen, oxygen, carbon, and nitrogen.

MARDI was built by Malin Space Science Systems. From what I could gather, the MARDI was not used by the Lander due to some integration issues.

The Canadian Space Agency (YAY Canada!) was responsible for the overall development of the meteorological station (MET). Two companies from Ontario, MD Robotics and Optech Inc., provided the instruments for the station.

The SSI served as the eyes of the Phoenix mission. SSI provided high-resolution, stereo, panoramic images of the Martian arctic. An extended mast holds the SSI, so the images were recorded from two meters above the ground.

MECA was built by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The instrument was used to characterize the soil by dissolving small amounts of soil in water. MECA determined the pH, the mineral composition, as well as the concentration of dissolved oxygen and carbon dioxide in the soil samples that were collected.

We would like to highlight some of the important moments during the mission:

August 4, 2007 – Delta II rocket launch from Cape Canaveral. The three-stage Delta II rocket with nine solid rocket boosters lifted off from Cape Canaveral, carrying the Phoenix spacecraft on the first leg of its journey to Mars.

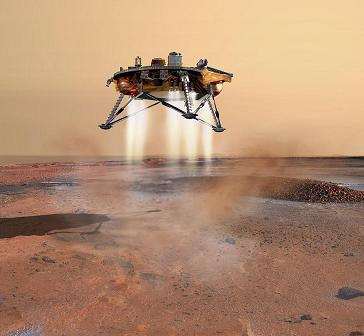

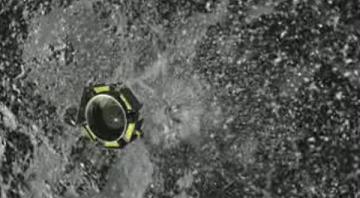

May 25, 2008 – Phoenix Mars Lander touchdown. The Phoenix entered the Martian atmosphere at 13,000 mph. It took 7 minutes for the Lander to slow down with the aid of a parachute and to land using its retrorockets. The mission team did not have to wait long before discovering ice because the blasts from the retrorockets had blown away the topsoil during landing and revealed ice patches under the lander.

November 2, 2008 – Last signal received from the Lander. On this date, communication was established for the last time with Phoenix. Due to the latitude of the landing site, not enough sunlight is available and the solar arrays are unable to collect the power necessary to charge the batteries that operate the instruments mounted on the Lander. At the landing site, the weather conditions are worsening.

November 10, 2008 – Mission declared completed. NASA declares that the Mars Phoenix Lander has completed a successful mission on the Red Planet. Phoenix Mars Lander has ceased communications after being operational for more than five months (the designed operational life of the mission was 90 days).

November 13, 2008 – Mission Honored. NASA’s Phoenix Mars Lander was awarded Best of What’s New Grand Award in the aviation and space category by Popular Science magazine.

The Mars Phoenix Lander made significant contributions to the study of the Red Planet. Phoenix verified the presence of water ice under the Martian surface, and it returned thousands of pictures from Mars. Phoenix also found small concentrations of salts that could be nutrients for life, it discovered perchlorate salt, and calcium carbonate, which is a marker of effects of liquid water.

Phoenix provided a mission long weather record, with data on temperature, pressure, humidity, and wind, as well as observations on snow, haze, clouds, frost, and whirlwinds.

Principal Investigator Peter H. Smith of the University of Arizona led the Phoenix mission. The project management was done at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the development at Lockheed Martin Space Systems in Denver. Other contributors were the Canadian Space Agency, the University of Neuchatel (Switzerland), the University of Copenhagen (Denmark), the Max Planck Institute (Germany), and the Finnish Meteorological Institute.

For more information about the Phoenix mission, check out the NASA Phoenix Mars Lander Page.

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS