Ed Belbruno, the first to use weak stability boundary theory to design trajectories for space missions, has agreed to answer some questions for OrbitalHub readers.

DJ: You graduated in mathematics from New York University, and received your PhD in mathematics from New York University’s Courant Institute. As a mathematician, how did you develop an interest in celestial mechanics?

Ed Belbruno: I was always interested in space since I was very young, going back to 4 years old. When I went to undergraduate school, also at NYU, I was a joint chemistry and mathematics major. At that time I was also interested in astrochemistry. When I got my BS, I went on to the Courant Institute and immediately wanted to get involved in an area of mathematics involved with space. I asked around, and found that there was a very famous mathematician there who was considered to be one of the leaders in the world in the subject, Juergen Moser. I learned that he was also a leader in a field called theoretical celestial mechanics. So, I asked to work with him and he agreed. For me it was great because I loved mathematics and I loved space. I am also an artist, and my early paintings involved a lot of space scenes. My being drawn to celestial mechanics was a natural thing.

DJ: I think of celestial mechanics as a precise discipline… the word CHAOS from the titles of the presentations you are giving would make any aerospace engineer nervous. Is this a misnomer or it is really the foundation for the new class of trajectories you designed?

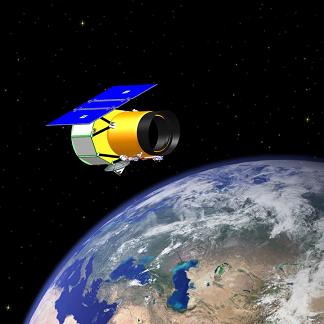

E.B.: When I arrived at JPL in 1986, I was previously an assistant professor of mathematics at Boston University. I arrived at JPL and found myself at a leading space center – to work on the following missions: Galileo, Cassini, Magellan, Ulysses. My job was to do trajectory design. I noticed that all these missions and all the others I saw in the past, relied mainly on Hohmann transfers which are straightforward trajectories found using algebra. They are very well behaved and linear in nature. There was nothing chaotic about them. I noticed that in the field of astrodynamics, which designs trajectories for spacecraft, that advanced mathematical techniques using a general subject called dynamical systems theory, which includes chaos theory, was never used. I figured if you could incorporate that into astrodynamics, new exciting low fuel trajectories could be found. No one at JPL really believed me, but in 1986 I started investigating whether or not one could use the subtle gravitational interactions between the Earth and Moon to get a spacecraft into orbit about the Moon without the use of rocket engines – that is, automatically. This had never been done before. I also found that chaos methods had to be employed to do this since the gravitational interactions between the Earth and Moon give rise to chaotic motions for a spacecraft. I succeeded in 1986 and found a way to do this for a mission study at JPL called LGAS – Lunar Get Away Special, where I found a 2-year route to the Moon with automatic capture at the Moon that was chaotic. This was the first time chaos was used for a lunar capture for a spacecraft – or capture at any planet. It was the first systematic use of chaos in astrodynamics as far as I know. The LGAS design was eventually used by the European Space Agency for their SMART-1 lunar mission in 2004. In 1991 I found a 3-4 month route to the Moon using automatic chaotic capture for Japan’s Hiten mission. This transfer first moves out to 1.5 million kilometers from the Earth, then falls back to the Earth-Moon system and into automatic ballistic capture about the Moon. This same transfer type is going to be used for NASA’s GRAIL mission in 2011. All these trajectories that go to automatic capture at the Moon are chaotic since they are very sensitive to small changes.

DJ: Was there any resistance from the scientific community when you first published the results of your research?

E.B.: Yes. When I first started designing routes to the Moon that employed automatic capture (or ‘ballistic capture”) back in 1986-1990 at JPL, that employed chaos as described above there was a good deal resistance, in spite of publishing papers and demonstrating actual trajectories via computer simulations. This is because no one had ever heard of this before, and also, chaos was a not a term that was desired to be associated with space travel. In 1990 I had a disagreement at JPL over this and found myself looking for another job. Luckily, soon, a couple of months after that while still at JPL, ready to leave for another job, I was able to take part in the rescue of a Japanese lunar mission, and get its spacecraft, Hiten, successfully to the Moon on one of these new transfers employing ballistic capture, that vindicated my work – and saved my career.

DJ: Are there any computational challenges that make the class of trajectories you designed difficult to compute? Is the lack of computational power the reason they are a recent development in celestial mechanics?

E.B.: Yes, they require more accuracy than is typically used since the motions involved are very sensitive in nature. So, different methods, other than classical optimization methods, have to be employed. These methods involve using ideas from chaos theory and dynamical systems and making use of regions that support chaotic motions called weak stability boundaries. Once the motions in these regions were better understood, then the methods have been refined and the trajectories can be more easily generated. More powerful computers were/are not necessary. What was necessary were new numerical methods.

DJ: I believe solar sails would match the profile of low-energy space missions. Have you ever considered applying the weak stability boundary theory in order to design trajectories for spacecraft propelled by solar sails?

E.B.: I agree that solar sails would be a great thing to use with these low energy trajectories. I have considered them and made some designs actually, but never designed any missions using them.

DJ: Considering your experience in designing low-cost trajectories for lunar missions, have you been contacted by any Google X-Prize team for assistance? How feasible would it be for a Google X-Prize team to use such a trajectory (costs aside, they would have to launch at least three months before any other team in order to make an attempt to win the prize)?

E.B.: Yes, I was on the so-called ‘Mystery team’ for the Google X-prize from latter 2007 to latter 08. The base design was to use one of these low energy transfers to the Moon of the type that Hiten used, described earlier, and that GRAIL is planning to use. I don’t know how feasible it would be to use this trajectory – certainly no more or less feasible than using a direct Hohmann transfer. It ultimately depends on the launch vehicle, which are very expensive. I don’t think the three months flight time is a factor since it is very unlikely that there will be that kind of time pressure considering how difficult it is to send something to the Moon for a private company.

DJ: What other space missions are you currently involved in? Can you provide a brief description?

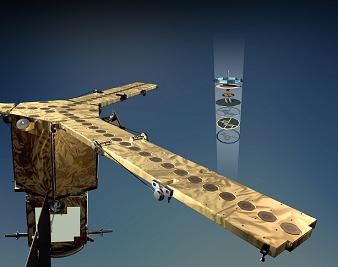

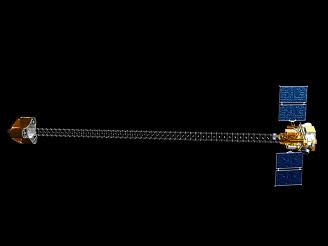

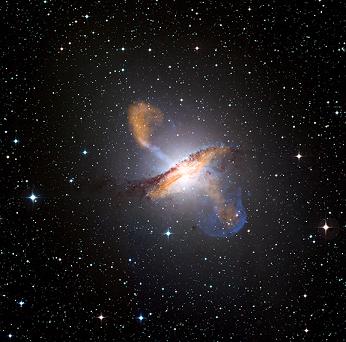

E.B.: I am involved, indirectly, with NASA’s STEREO solar science mission in the sense that they have recently redirected that mission to do an excursion to L4, L5 of the Earth-Sun to try and verify a theory of Richard Gott and myself on the origin of the Moon. This theory was published by Gott and myself in 2005 (see http://www.edbelbruno.com) in the Astronomical Journal entitled, Where Did the Moon Come From? In that paper we hypothesized that the giant Mars-sized impactor that is thought to have hit the Earth to form the Moon, billions of years ago (that Hayden has a fabulous show on), actually originated at special locations in space. These locations are called Earth-Sun equilateral L4, L5 points, 93 million miles from the Earth in either direction, on the Earth’s orbit. The impactor is called Theia. It is felt that if our theory is correct that residual material and perhaps asteroids exist near L4, L5. To verify this, the STEREO mission, consisting of two spacecraft, are being redirected to go to these points to investigate the possible remains of the mysterious planet called Theia that may have been there long ago. The NASA press release explains this in detail. The spacecraft are due to arrive at L4, L5 in September, October this year and are currently approaching these locations.

DJ: It is not often you meet someone who is both an artist and a mathematician. How do these roles complement each other?

E.B.: When I do paintings, I find that I have to completely turn off any logical mathematical way of thinking and work on a subconscious level. This is exactly the opposite of working mathematically where you have to be very logical and work mostly with the conscious part of your mind. These two processes are totally different. There is a little subconscious thought when doing mathematical/scientific work, of course, but you have to pay close attention to deductive reasoning. In doing a painting, especially abstract expressionist painting, you have to avoid as much as possible deductive reasoning and be very spontaneous without thinking, which would ruin the painting. I have found it challenging to work in these two different ways – but now I can do it fairly easily.

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS