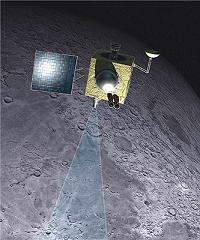

We presented in a previous post the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) mission. The goals of the LRO mission are to map the lunar resources and to create a detailed 3D map of the lunar surface in preparation for future NASA missions to the Moon. However, NASA is not the only space agency that has high hopes regarding the exploration of the Moon. The Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) is another agency heavily involved in space activities.

Interest in undertaking a lunar scientific mission was sparked at a meeting of the Indian Academy of Sciences in 1999. One year later, the Astronautical Society of India made a recommendation supporting the idea.

The ISRO formed a National Lunar Mission Task Force that involved leading Indian scientists. The Task Force provided an assessment on the feasibility of such a mission. The mission, called Chandrayaan-1, was approved in November 2003 for an estimated cost of $83 million USD.

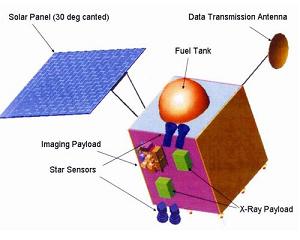

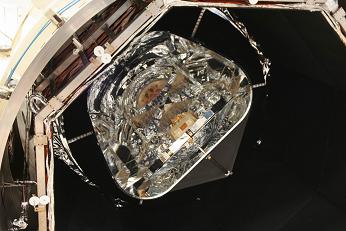

The Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft is a 1.5 meter cube with a weight mass of approximately 523 kg. The spacecraft bus is based on an already developed meteorological satellite. Chandrayaan-1 will carry a 30 kg probe that will be released to penetrate the lunar surface. The power for the onboard systems is generated by a solar panel. The 750 watts generated by the solar panel will be stored by the rechargeable batteries onboard the spacecraft. Maneuvering in the lunar orbit is done using a bipropellant propulsion system.

The scientific payload contains a diverse collection of instruments. The instruments were designed and developed by ISRO, ESA, NASA, and the Bulgarian Space Agency.

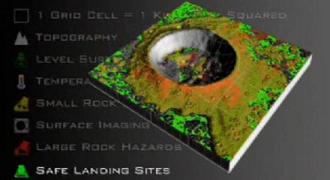

There are two instruments that will map the surface of the Moon: the Terrain Mapping Camera (TMC) will produce a 5 meter resolution map of the surface, and the Lunar Laser Ranging Instrument (LLRI) will scan the lunar surface and determine the surface topography.

The X-ray spectrometer onboard the spacecraft has three components: the Imaging X-ray Spectrometer (CIXS), the High Energy X-ray/gamma ray spectrometer (HEX), and the Solar X-ray Monitor (SXM). The X-ray spectrometer will measure the concentration of certain elements on the lunar surface as well as monitor the solar flux in order to normalize the results of the measurements taken.

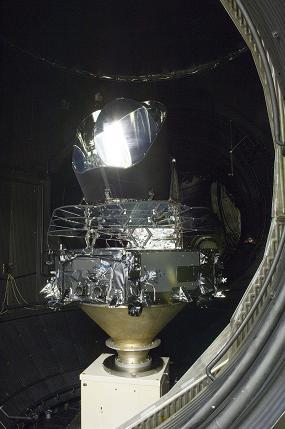

The mineralogical configuration of the surface will be mapped by four instruments: the Hyper Spectral Imager (HySI), the Sub-keV Atom Reflecting Analyzer (SARA), the Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3), and the Near-Infrared Spectrometer (SIR-2).

The Radiation Dose Monitor (RADOM-7) will record the radiation levels in the lunar orbit.

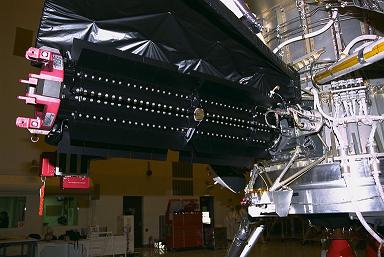

ISRO has two operational launch vehicles: the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) and the Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV). For Chandrayaan-1, ISRO has chosen to use PSLV as a launch vehicle. The PSLV developmental flights were completed in 1996 and the rocket has had 12 successful missions since then. PSLV is 44.43 meters tall and has a weight of 294 tonnes at launch. It can inject a payload of 1,000 kg – 1,200 kg into a polar orbit.

The launch of the Chandrayaan-1 mission is scheduled for the end of October 2008. The PSLV rocket will take off from the Satish Dhawan Space Center in Sriharikota on the southeast coast of India. The transfer to the lunar orbit will take approximately five days and after additional maneuvers the spacecraft will reach its final polar orbit, 100 km above the surface. The spacecraft will be operational for two years.

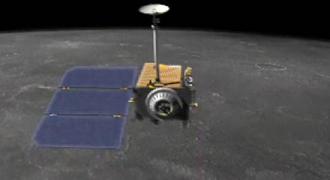

The Chandrayaan-1 mission opens the door to future lunar missions. ISRO has already committed to a second Chandrayaan mission that will land a rover on the surface of the Moon. The rover will perform a number of experiments on the lunar surface and the results will be relayed to Earth by the Chandrayaan-2 orbiter.

We will come back with more details about the Chandrayaan-1 mission as the events unfold. Please stay tuned on the OrbitalHub frequency.

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS