|

| Credits: NASA |

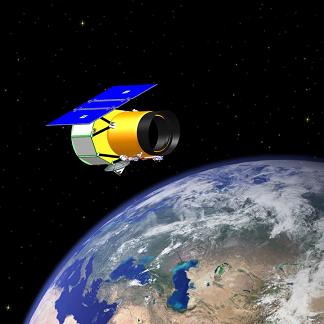

Kepler is the first NASA mission capable of finding terrestrial exo-planets. Of particular interest are the planets orbiting in the so-called habitable zone, where conditions are met so that liquid water can exist on the surface of the planet.

The observations made so far have brought clear evidence that planets orbiting around other stars are a common thing, rather than the exception to the rule. Due to the limitations of present technology, only gas giants, hot-super Earths in short period orbits, and ice giants have been discovered.

The Kepler mission, part of NASA’s Discovery Program, is designed to survey a portion of our region of the Milky Way. Kepler will survey a large number of stars, and explore the structure and diversity of many planetary systems.

The scientific objectives of the mission are very ambitious: determine the fraction of terrestrial planets in or near the habitable zone, determine the distribution of sizes and the orbits of exo-planets in the surveyed planetary systems, determine reflectivity, size, and density of short-period giant planets, estimate how many planets are in multiple-star systems, and determine the characteristics of the stars that have planets orbiting around them. Scientists hope to discover additional members of the planetary systems surveyed using other indirect techniques.

|

| Credits: NASA/Ball Aerospace |

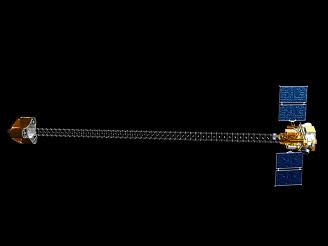

The duration of the mission must be selected to allow the detection and confirm the periodic nature of the planet transits in or near the habitable zone. Due to the characteristics of orbits of such planets, a lifetime of three and a half years (as currently envisioned) would allow a four-transit detection of most orbits up to one year in length and a three-transit detection of orbits of length up to 1.75 years.

The mission lifetime will be extendible to at least six years. The extension will permit the detection of planets smaller than Earth with two-year orbits.

Kepler will be inserted in an Earth-trailing heliocentric orbit, then the spacecraft will slowly drift away from Earth. The selected orbit offers a very stable pointing attitude, and it avoids the high radiation dosage associated with an Earth orbit. However, Kepler will be exposed occasionally to solar flares.

The communication protocol with the spacecraft includes establishing contact twice a week for commanding, health, and status, and science data downlink contact once a month.

|

| Credits: Jon Lomberg |

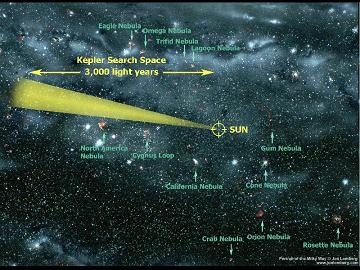

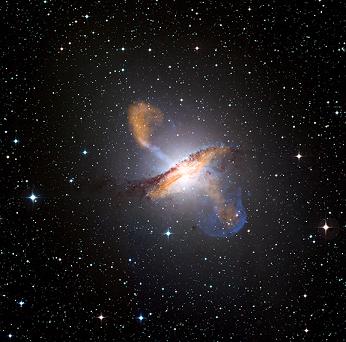

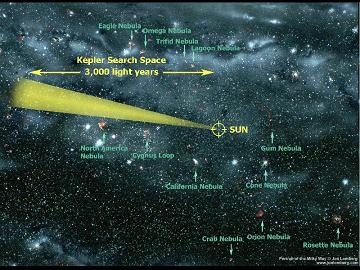

There are two requirements that dictated the selection of the target field. The first requirement is the ability to monitor continuously the stars surveyed because transits last only a fraction of a day. This can be achieved by having the field of view out of the ecliptic plane, so the Sun will not interfere with the observations at any time during the year. The second requirement is to have the largest possible number of stars in the field of view.

To meet both requirements, a region in the Cygnus and Lyra constellations of our galaxy has been selected as the field of view.

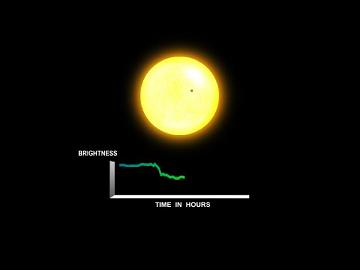

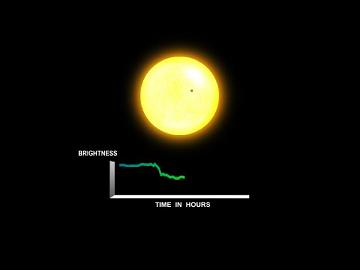

Kepler will use the transit method for detecting exo-planets. The sensitivity of the photometer will allow the discovery of terrestrial exo-planets (planets comparable in size and composition to Earth that are orbiting other stars).

The transit occurs when a planet passes in front of its star as viewed by an observer. Depending on the size of the planet, the change in the brightness of the star has different amplitudes. Transits of terrestrial planets cause a change in the star’s brightness of about 1/10,000, and they last from two to sixteen hours.

|

| Credits: NASA |

Changes in star brightness that are produced by a planet transit must be periodic, and all transits produced by the same planet must cause the same variation of brightness and last the same amount of time.

Of course, the case when two or more planets are in transit at the same time must be considered, and this can make the detection method a little bit more complicated.

The method allows for the calculation of the orbit, the mass, and the characteristic temperature of the exo-planet. Once we know the characteristic temperature of an exo-planet, the question of whether or not the planet is habitable (by our standards) can be answered.

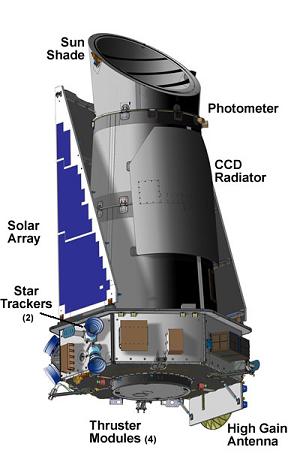

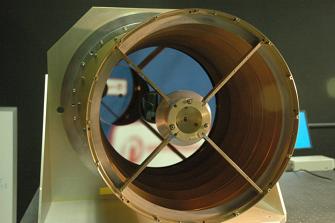

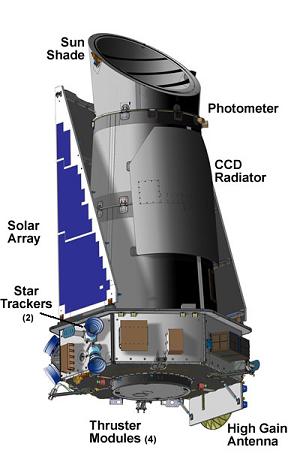

The Kepler instrument is a special telescope called photometer or light meter. The telescope has a very large field of view for an astronomical telescope, 105 square degrees. The primary mirror of the telescope is 0.95 m in diameter. The telescope needs a large field of view because it has to continuously monitor the brightness of more than 100,000 stars for the duration of the mission.

|

| Credits: Ball Aerospace |

The photometer is composed of one instrument, which is an array of charge-coupled devices (CCD), 42 in total. Each CCD is 50mm x 25mm and has 2200 x 1024 pixels. Data from the individual pixels that make up each star are recorded continuously and simultaneously.

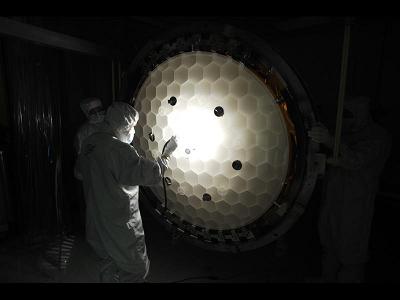

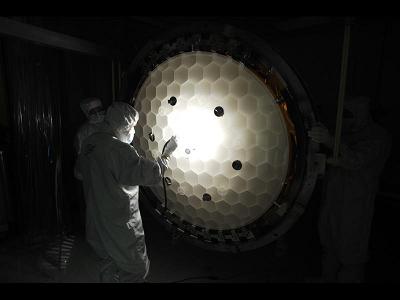

The primary mirror of the photometer was coated with enhanced silver, which allows more light to reach the telescope’s detectors.

The spacecraft provides power, attitude control, and telemetry for the photometer. The mission requirements contributed to the simple design of the spacecraft. The only moving parts are the reaction wheels used to control the attitude of the spacecraft.

The launcher selected for the mission is Delta II. Delta II is a versatile launcher, and can be configured in two or three-stage vehicles in order to accommodate a variety of requirements.

Ball Aerospace is the prime contractor for the Kepler mission, building the photometer and the spacecraft, as well as managing the system integration and testing of the spacecraft. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory is managing mission development, while NASA Ames Research Center is responsible for ground system development, mission operations, and science data analysis.

Once the first observation results are downloaded from Kepler and made available to scientists, we will be able to place our solar system within the context of planetary systems in our galaxy.

The launch of Kepler is planned for March 5, 2009. For more information about the Kepler mission, you can visit the Kepler mission web page.

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS

Subscribe to blog posts using RSS